Ensuring Blended Finance can mobilise private finance, particularly in the Least Developed Countries and towards Social Sectors, will require a systemic and transformational approach.

Even before the arrival of COVID-19, the SDG financing gap was significant. The private sector is an important contributor to SDG delivery and has increasingly been mobilised with the support of blended finance approaches. Blended finance has been defined as the strategic use of development finance for the mobilisation of additional finance towards sustainable development in developing countries[1]. In 2018-19, official development finance mobilised nearly $50bn of private sector finance for development[2]. However, this amount is not enough. In particular, in countries where development finance flows, especially ODA, become a critical source to finance social services, the current share falls short from commitments. The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on developing countries are increasing financing needs while reducing available resources.

Without swift global action, years of progress made towards SDG targets could be undone. Blended finance has an important role in unlocking and channelling commercial finance towards sustainable development. Commercial capital is key as there is a lot available and channelling just one percent of total global financial assets (estimated at $382tn), could bridge the existing SDG financing gap, at $2.5tn annually[3]. Essentially, blended finance allows for financial returns to investors while addressing investment barriers by improving the risk-return profile of investments. Blended finance operates as a market-building instrument that provides a bridge from reliance on development financing towards commercial finance, critical to ensuring SDG compliant sectors and markets get adequate financing for them to develop.

Blended Finance Needs to Grow and Be Redirected to the Countries and Sectors Most In Need

Despite the volumes mobilised the direction of the financing has been skewed towards middle-income countries and commercial sectors (like banking, finance, and energy). While Less Developed Countries (LDCs) are disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 crisis, they continue to receive the lowest share (despite a modest increase in overall volume) of private finance mobilised by official development finance interventions.

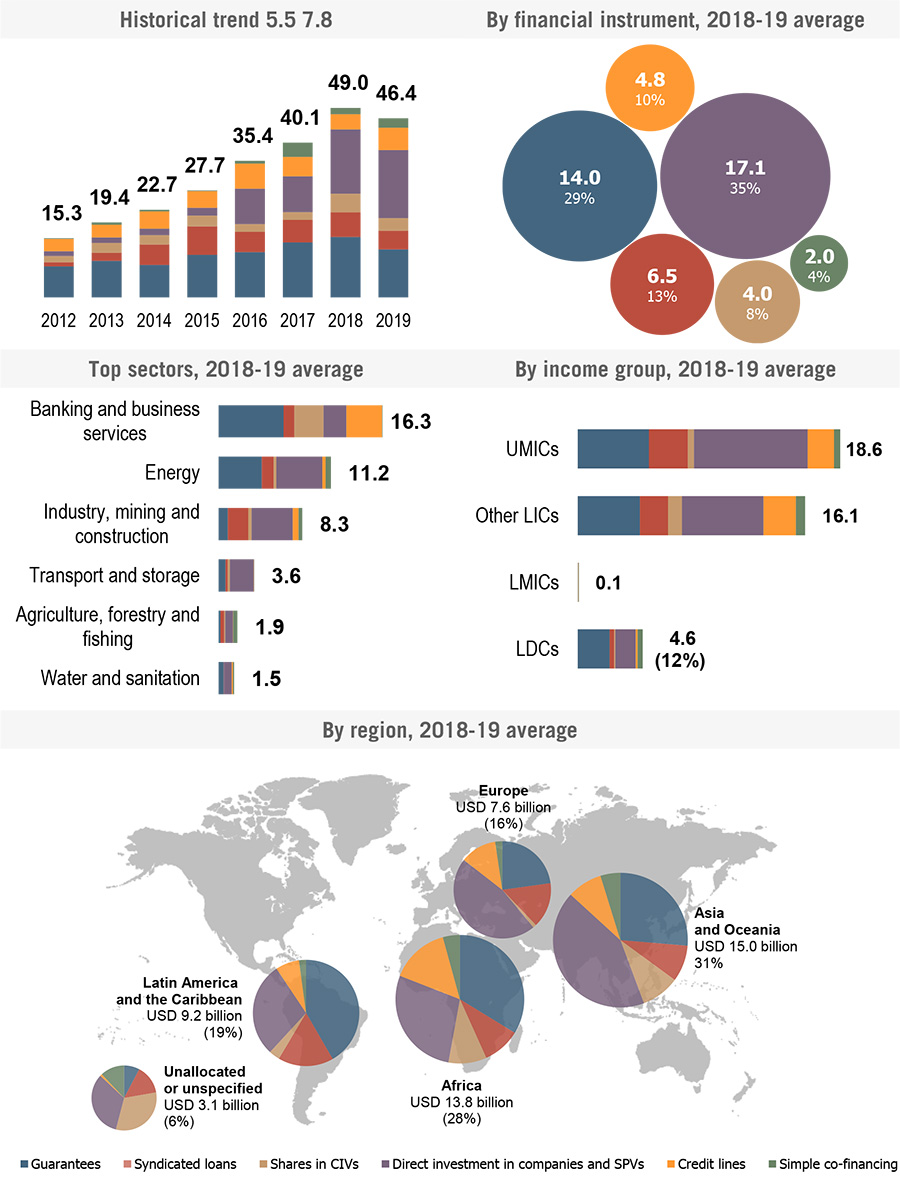

Figure 1: Amounts mobilised from the private sector – main trends (USD billion). Note: The percentage of private finance mobilised for the LDCs is calculated as share of country-allocable private mobilisation. Source: OECD (2021).

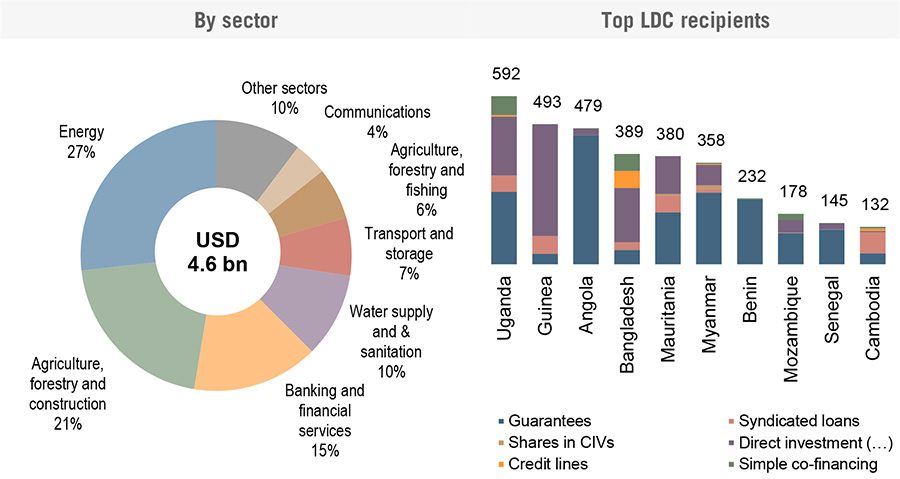

From a very low base, the mobilisation trends are positive with private finance mobilised for LDCs and other LICs increasing from $3.8bn in 2018 to $4.6bn in 2019. The share of LDCs and other LICs private finance mobilised increased from 7.5 percent to 12 percent as shown in Figure 1. However, the financing remains far below what is needed, as the SDGs are often the widest in the LDCs. This is despite the fact that the LDCs are home to over one billion people, about 14% of the world population across 46 countries. Furthermore, the vast majority of financial resources mobilised, $16.3bn, targeted the banking and business services with only $1.5bn mobilised in the water and sanitation sector.

Building back better from the pandemic requires a multilateral and multifaceted response that advances a transformational and systemic approach. It needs to include innovative financial tools and risk-mitigation instruments, that link that to policy actions, like coordinated engagement between the private sector, local governments, and multilateral development banks (MDBs) and development finance institutions (DFIs). Appropriate coordination and the effective use of blended finance mechanisms could ensure that funds are directed towards projects that are aligned with the SDGs, particularly those in the social sector that are often excluded by private investors or cast aside in favour of opportunities that are more commercial. As the recent OECD–UNCDF Report highlighted[4], Blended Finance has the potential, among other purposes, to leverage digital technologies; finance small and medium-sized enterprises in the “missing middle” (gap); and address market failures that prevent the LDCs from financing their development needs and reaching the most vulnerable[5].

In response to the economic and financial reverberations, the short-term approach has been shoring up development finance portfolios. The general risk aversion of DFIs makes it particularly challenging for them to attract even more risk-averse commercial investors into LDCs and exploring new investable opportunities in the near term as long as the pandemic is ongoing.

In the medium- to long-term, blended finance can play a critical role in the COVID-19 recovery by stimulating economic recovery and increasing resilience to future shocks, both financial and social.

Figure 2: Private finance mobilised in the LDCs – main sectors and recipients, 2018-19 average $billions. Source: OECD (2021).

Meeting the significant sustainable investment needs in the LDCs post-COVID-19 will require a strategic assessment of how blended finance can be deployed at scale. Overall, this could mean moving away from a focus on individual transactions towards the greater use of blended finance funds and facilities. A portfolio approach could also help to create larger deals, to increase diversification (in turn, reducing risks), and make assessment and approval processes more cost-effective. DFIs and MDBs may need to revise their risk–return threshold in order that greater risks and, ultimately, volumes of blended finance can be directed to the LDCs and social sectors.

In order for funds to reach where they are needed most, there must be coordination between governments and other relevant stakeholders, in particular DFIs, in the LDCs who can help direct funds to the sectors most in need. Especially in social sectors, where investors tend to be risk-averse, the role of DFIs can help to build investors’ confidence and mitigate or reduce the risk. Understanding local capacity for deployment and ensuring a local perspective is crucial to the success of the investment and project’s impact. Therefore, developing countries themselves must be empowered to have a stronger role in diverting blended finance to social sectors and the LDCs. Social projects are likely to be closer to government actors, require more consultation and greater understanding of social needs on the ground. Moreover, for projects to receive local currency financing, local ownership will be critical. Local pension funds and other local sources of finance should invest in these social sectors, which are often critical for delivering the SDGs particularly in the context of the LDCs. Local DFIs and other financial actors in the LDCs can help in developing the blended financing structures necessary to deliver social projects.

To ensure the transition towards the more effective use of Blended Finance, a systemic and transformational approach is needed. Without significant change, the required volumes of Blended Finance will not be achieved, and the private finance mobilised will not be directed to the LDCs and social sectors.

The Role of the G20

The G20 is well positioned to advance global efforts towards a more equitable and sustainable recovery from the economic shocks of the pandemic. The group has committed, under the Financing for Sustainable Development Framework endorsed in 2020 under the Saudi Arabian Presidency, to mobilising all sources of finance, including blended and private sector financing towards the alignment and impact of the SDGs[6]. As part of the G20 Development Working Group (DWG) work under the Italian G20 Presidency in 2021, G20 members have further advanced awareness about innovative finance instruments. The Presidency produced a stock take report on how to scale up green, social and sustainability bonds to finance climate related activities and SDG-related projects in developing countries. In parallel, the G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group has worked on reporting and regulations for private finance mobilised towards climate finance and could look at GSS bonds in the future. Greater synergies could be found between these two areas of work, as blended finance mechanisms are used in the issuance of green and other thematic bonds, and lead to the mobilisation of new private finance.

Importantly, blended finance can play a key role in supporting the LDCs to mobilise resources for the medium to long-term recovery. For blended finance to be an effective instrument for the COVID-19 recovery, the wide range of actors involved (donors, DFIs, multilateral development banks, impact and commercial investors, local financial institutions, national and local governments, etc.) should focus on supporting the institutional capacity of countries and building pipeline projects that linked to national development priorities. This includes job creation, SME-development, an emphasis on gender equality, support health systems, and target sectors that are critical for inclusive, resilient and sustainable development.

In summary, four key areas for further work are:

- Use blended finance strategically to develop sustainable domestic market systems and build the capacity of local capital market actors.

- Design innovative structures that target the hardest to reach and most underserved areas

- Improve impact management and measurement, and promote transparency

- Bring blended finance to (large) scale through systemic and transformational approaches

Indonesia assumed the G20 Presidency on 1 December 2021, and will hold the G20 presidency throughout 2022. Indonesia has already confirmed its plans to develop G20 Principles on Scaling-up Private and Blended Finance in the G20 DWG. The OECD will support Indonesia in producing practical and actionable guidance for developing countries on how to scale up the use of private and blended finance, building on existing work. This has the potential to address some of the coordination barriers and lack of transparency around deals that have marred blended finance mechanisms in the past. The OECD and Indonesia will work in tandem to identify gaps and challenges faced by developing countries and the LDCs, and identify what capacity would be needed to allow blended finance to support the local economy and local capital markets.

References

[1]OECD (2018), “Blended finance Definitions and concepts”, in Making Blended Finance Work for the Sustainable Development Goals, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264288768-7-en.

[2] OECD (2021). Amounts mobilised from the private sector by official development finance interventions in 2019-19: Highlights, https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/mobilisation.htm (accessed on 26 November 2021)

[3] Speech by the OECD Secretary General (https://www.oecd.org/about/secretary-general/private-finance-for-sustainable-development-conference-paris-january-2020.htm)

[4] https://www.oecd.org/finance/blended-finance-in-the-least-developed-countries-2019-1c142aae-en.htm

[5] OECD/UNCDF (2020) Blended in Least Developed Countries: Supporting a Resilient COVID-19 Recovery, https://doi.org/10.1787/57620d04-en (accessed 26 November 2021)

[6] G20 Development Ministers Communiqué (2021), G20-Development-Communique.pdf (accessed 26 November 2021)

About the Authors

Author: Haje Schütte

Haje Schütte is Senior Counsellor & Head of Financing for Sustainable Development Division of the OECD Development Co-operation Directorate. His work focuses on how to address the dual challenges at the core of the 2030 Agenda, i.e. mobilising unprecedented volumes of resources, and leaving no-one behind.

Author: Ibu Raden Siliwanti

Ibu Raden Siliwanti is the Director for Multilateral Funding (Cooperation Bappenas/Indonesian, G20 DWG Team, Ministry of National Development Planning/Bappenas).

By Haje Schütte and Ibu Raden Siliwanti. Contributing authors: Felicia Rodriguez, Wiwien Apriliani (Indonesian G20 DWG Team), Rolf Schwarz, Tomas Hos and Paul Horrocks